George Inness Biography In Details

Youth

George Inness was the fifth of thirteen children born to John Williams Inness, a farmer, and his wife, Clarissa Baldwin. His family moved to Newark, New Jersey when he was about five years of age. In 1839 he studied for several months with an itinerant painter, John Jesse Barker. In his teens, Inness worked as a map engraver in New York City. During this time he attracted the attention of French landscape painter Regis Francois Gignoux, with whom he subsequently studied. Throughout the mid-1840s he also attended classes at the National Academy of Design, and studied the work of Hudson River School artists Thomas Cole and Asher Durand; "If", Inness later recalled thinking, "these two can be combined, I will try."

Concurrent with these studies Inness opened his first studio in New York. In 1849 Inness married Delia Miller, who died a few months later. The next year he married Elizabeth Abigail Hart, with whom he would have six children.

Early career

In 1851 a patron named Ogden Haggerty sponsored Inness' first trip to Europe to paint and study. Inness spent more than a year in Rome, during which time he rented a studio above that of painter William Page, who likely introduced the artist to Swedenborgianism.

During trips to Paris in the early 1850s, Inness came under the influence of artists working in the Barbizon school of France. Barbizon landscapes were noted for their looser brushwork, darker palette, and emphasis on mood. Inness quickly became the leading American exponent of Barbizon-style painting, which he developed into a highly personal style. In 1854 his son George Inness, Jr., who also became a landscape painter of note, was born in Paris.

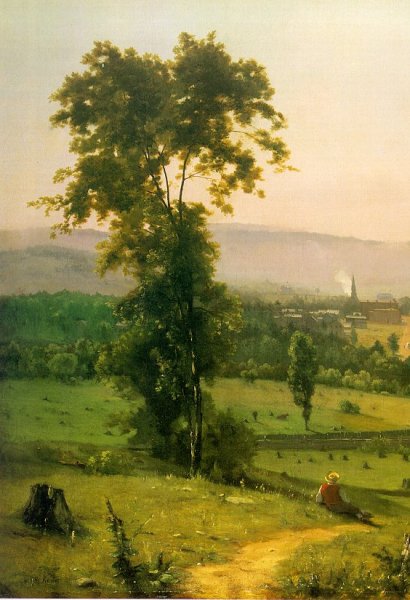

In the mid-1850s, Inness was commissioned by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad to create paintings which documented the progress of DLWRR's growth in early Industrial America. The Lackawanna Valley, painted ca. 1855, represents the railroad's first roundhouse at Scranton, Pennsylvania, and integrates technology and wilderness within an observed landscape; in time, not only would Inness shun the industrial presence in favor of bucolic or agrarian subjects, but he would produce much of his mature work in the studio, drawing on his visual memory to produce scenes that were often inspired by specific places, yet increasingly concerned with formal considerations.

Maturity

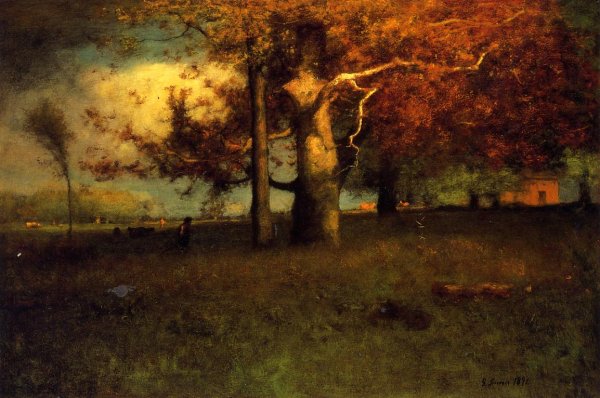

The work of the 1860s and 1870s often tended toward the panoramic and picturesque, topped by cloud-laden and threatening skies, and included views of his native country (Autumn Oaks, 1878, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Catskill Mountains, 1870, Art Institute of Chicago), as well as scenes inspired by numerous travels overseas, especially to Italy and France (The Monk, 1873, Addison Gallery of American Art; Etretat, 1875, Wadsworth Atheneum). In terms of composition, precision of drawing, and the emotive use of color, these paintings placed Inness among the best and most successful landscape painters in America.

Eventually Inness' art evidenced the influence of the theology of Emanuel Swedenborg. Of particular interest to Inness was the notion that everything in nature had a correspondential relationship with something spiritual and so received an "influx" from God in order to continually exist.

Another influence upon Inness' thinking was William James, also an adherent to Swedenborgianism. In particular, Inness was inspired by James' idea of consciousness as a "stream of thought", as well as his ideas concerning how mystical experience shapes one's perspective toward nature.

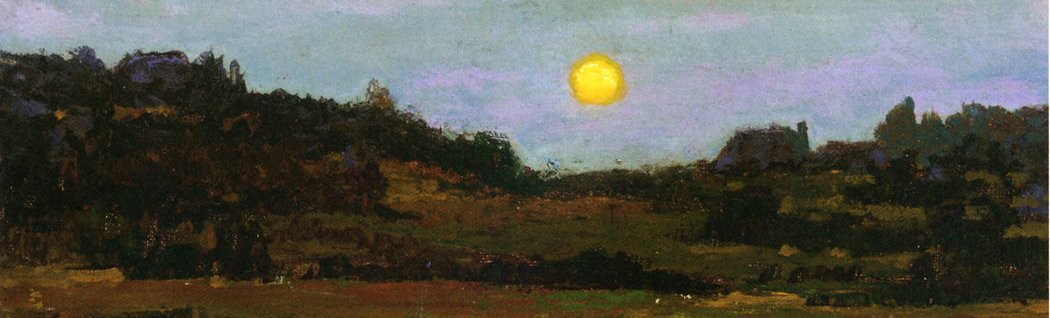

After Inness settled in Montclair, New Jersey in 1885, and particularly in the last decade of his life, this mystical component manifested in his art through a more abstracted handling of shapes, softened edges, and saturated co.

It is this last quality in particular which distinguishes Inness from those painters of like sympathies who are characterized as Luminists.

In a published interview, Inness maintained that "The true use of art is, first, to cultivate the artist's own spiritual nature." His abiding interest in spiritual and emotional considerations did not preclude Inness from undertaking a scientific study of color, nor a mathematical, structural approach to composition: "The poetic quality is not obtained by eschewing any truths of fact or of Nature...Poetry is the vision of reality."

Inness died while in Scotland in 1894. According to his son, he was viewing the sunset, when he threw up his hands into the air and exclaimed, "My God! oh, how beautiful!", fell to the ground, and died minutes later. (From Wikipedia)